Passive Restoration: Protecting Our Forest-Meadow Soil Reservoirs

- Nov 30, 2017

- 4 min read

A forest meadow in the Marble Mountain Wilderness collects snows and recharges the “sponge”

It is late November in the Klamath Mountains Bioregion[ii] and snow has begun to accumulate in the high country. For the next six months snow will rule the high mountains and few humans will venture there. While martens hunt in the subnivian space[iii] and the snow grows deeper, water seeps into cracks and fissures in rocks, into the many downed logs which litter unlogged forests and into sponge-like forest and meadow soil, filling the millions of tiny spaces found there with water.

With the coming of springtime warmth, the snowpack begins to melt. Meltwater swells mountain streams and the rivers below enabling Spring Chinook salmon to reach the deep, cold pools in which they will spend the summer. The springtime flood also enables Steelhead and resident trout to spawn higher in our watersheds than would otherwise be possible.

But long after the snowpack is gone, healthy forest and meadow soil continues to slowly yield the water stored in its many pores, sustaining both streamflow, salmon and the water supply on which humans depend through the long dry season. The soil acts like a sponge soaking up water, forming vast reservoirs. But like the sponge in your kitchen, forest and meadow soil can be compressed and compacted, damaging its water storage capacity, increasing flood flows and decreasing dry-season streamflow, also known as baseflow.

Logging, and particularly logging with bulldozers and dragging logs via cables to roads and landings, compacts forest soil damaging its water holding capacity. Livestock grazing can also degrade the health and water holding capacity of soil, particularly the soil underlying the wet meadows, springs, seeps, fens and willow wetlands found at higher elevation within western national forests. Because cattle grazing on public land weigh more than a ton (up to 1500 pounds), the season-long grazing without herding practiced on most western public land severely compacts meadow soil and lowers the water table, thereby reducing the water holding capacity of the meadows.

Real Restoration

The impact of bad logging and unmanaged cattle grazing on the cold baseflows on which salmon and other fishes depend throughout the summer has, for the most part, been ignored by public land managers, tribes, restoration councils and others who expend millions of taxpayer dollars each year to “restore” our streams and salmon. But so long as the water holding capacity of forest and meadow soil continues to be degraded, the active restoration these government and community organizations engage in and fund cannot successfully restore salmon and other Public Trust[iv] stream resources. For restoration to be effective, the activities causing degradation must end as well. Ending the activities which cause resource degradation is known as passive restoration.

The National Marine Fisheries Service, California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and Regional and State Water Boards are responsible for assuring and that water supplies are protected. Yet these regulatory agencies continue to allow bad logging and poorly managed headwater grazing to damage our mountain forest and meadow soil reservoirs. That ongoing and cumulative degradation of the sponges is preventing recovery of healthy streamflow and healthy salmon runs. Until we as a society insist that those practices, including bad logging and irresponsible grazing, which are the root causes of stream degradation and poor salmon survival finally end, active restoration will continue to fail to achieve its core objectives.

That’s why EPIC, EPIC’s allies and The Project to Reform Public Land Grazing, which EPIC sponsors, focus on ending those practices which damage Northwest California’s and the West’s headwater forest and meadow reservoirs. By insisting on passive restoration, we compliment the work of tribes and restoration groups, rendering the active restoration in which they engage more effective. When you support EPIC you are supporting those efforts, including protecting the vast forest and meadow reservoirs which sustain the water supply on which humans, salmon and healthy streams depend.

Thanks for your support!

Felice Pace, Coordinator

###

[i] The Project to Reform Public Land Grazing in Northern California was founded in 2009 to document the bad public land grazing management that has resulted in violation of water quality standards in the very headwater streams that should have the highest water quality and to advocate for regular herding and other modern grazing management practices which, if required, would vastly improve water quality and flows in public land headwater streams.

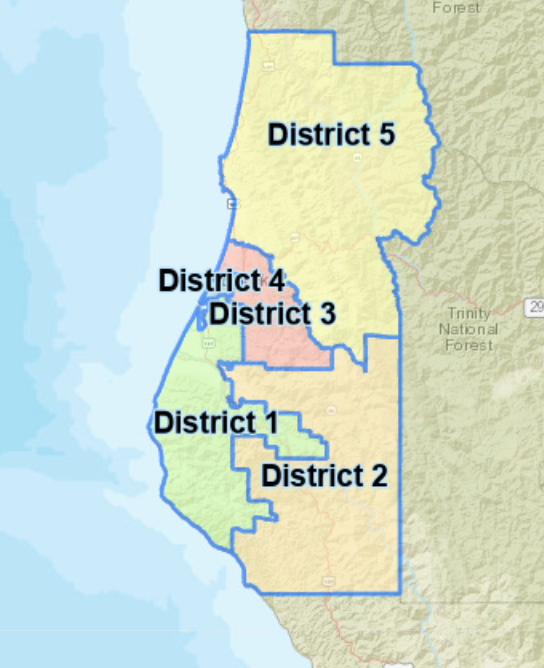

[ii] The Klamath Mountains Bioregion extends from Snow Mountain in the Mendocino National Forest to the Rogue and Umpqua River Divide in SW Oregon. It is also known as the Klamath-Siskiyou Bioregion. The Siskiyou Mountains are a prominent East-West running range of the Klamath Mountains.

[iii] The subnivian space is a thin air layer found between the covering snow and the surface of the soil and its vegetative debris.

[iv] That water, as well as the fish and wildlife which depend on water, are the common heritage of all humans, and therefore can not be owned and must be shared, has been recognized in western law since the days of the Roman Emperor Justinian. Coming to us via English and US Common Law, the Public Trust Doctrine holds that water, fish and other resources dependent on water are the common heritage of all humans. The PTD also guarantees right of access to all streams within the mean high water level.

Comments