One Step Closer To National Forest Plan Revisions

- Aug 10, 2020

- 2 min read

The Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), just got one step closer to revising forest plans throughout the Northwest. The Bioregional Assessment (BioA) spans about 24 million acres across 21 National Forests that are primarily within the range of the northern spotted owl covered under the Northwest Forest Plan. The BioA is a review of the current conditions and trends across a broad regional landscape and will serve as a foundation for land management plan revisions.

The National Forest Management Act requires that every national forest develop and maintain a land management plan, known as forest plans. These individual plans set direction for the landscape and include- desired conditions, non-discretionary standards and guidelines, monitoring plans and wilderness and Wild and Scenic River recommendations. The national forests of the Northwest are well overdue for updates, which are guided by the 2012 Planning Rule.

The ninety-page BioA document includes an overview of management recommendations, what is working well, challenges and opportunities for change and next steps.

The stated management recommendations include: maintaining and restoring ecosystem characteristics; addressing the dynamic nature of ecosystems to respond to uncertainties; updating and integrating aquatic strategies; reducing invasive species; prioritizing community and firefighter safety; recognizing that fire is a natural process which has an important role in reducing risk of uncharacteristic fire and promoting ecosystem health; expanding timber harvest as a restoration tool; evolving from single species focus; promoting active management; and recognizing the social and economic benefits from recreation.

What is working well? The BioA in summary concludes— the reserve network of older forests, riparian areas, roadless, wilderness and Wild and Scenic River designations has worked to maintain the ecological integrity of our forests. Our national forests are also working to provide clean water, carbon sequestration, traditional ecological resources, and relatively stable timber production, other forest products and outdoor recreation. It also claims that overall the loss of old growth habitat from timber harvest has been “stemmed”.

The “need for change” chapter can be summed up by stating the agency will seek to justify forest extraction in every way possible, that we need logging a.k.a. “active management” by calling it restoration. There are multiple catchy explanations or “needs” such as: 18 million acres lack structural diversity and resilience and do not contribute to ecological integrity; 10 million acres need some type of restoration; 7 million acres need disturbance restoration; 5 million acres in old-growth forest, ungulate cover, wildlife habitat, and scenic corridors have multiple plan objectives that inhibit active management to reduce susceptibility to insects and disease; and 2 million acres have plan direction that emphasizes timber production and these acres need active management.

The BioA largely tiers to the 2018 USDA Scientific Synthesis, which was the previous step in forest plan revisions. Both of these documents lean heavily on in-house agency science while dismissing independent and best available science. The revisions, in their beginning stages, are already highly controversial. While this step in the forest planning is not open to public comment there will be “public engagement opportunities” coming soon.

The next step is the Forest Assessment stage, where individual forest roles and contributions will be defined. Candidate stretches for Wild and Scenic River designation will be identified. Wilderness inventory will be constructed and potential species of conservation will be determined.

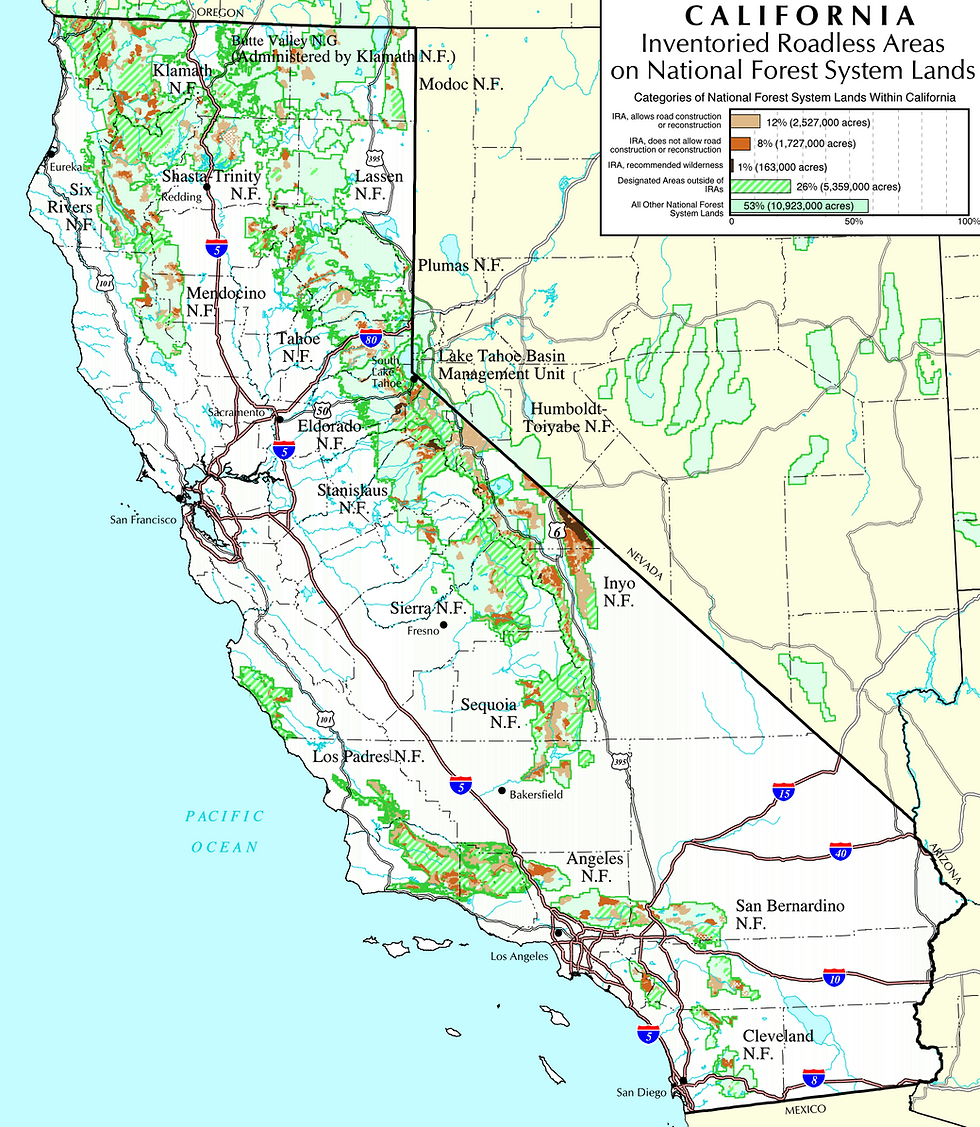

We are still years away from seeing any formal revised plans. However, there is discussion that the Northern California national forests will be the first out of the starting gate due to the influence of wildfire. EPIC will continue to strategize with our state and regional conservation networks to advocate for the protection of clean water, carbon storage, intact old-growth and mature forests, region-wide habitat connectivity for plants and wildlife and real restoration of our public lands.

Comments