Bringing the California Condor Home

- May 30, 2019

- 3 min read

Yurok Tribe Wildlife Program Photo by Chris West.

The EPIC team is excited to share with you the most recent update on the efforts to bring the condor back to northern California. The Yurok Tribe, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have been working together to create a comprehensive reintroduction program to assure their long-term health and survival. The environmental assessment is open for public comment until June 4. The plan is expected to establish a nonessential experimental population in northern California, northwest Nevada and Oregon. EPIC supports the efforts and sees this current push as vital to restoring this species to its natural habitat.

There are two types of condors, the Andean of South America and the California condor. Both have a significant and ancient history throughout the West. Revered by many nativetribes, they play an important role in several traditional myths. In Yurok tradition the condor remains a crucial part in ceremonies to renew the world and fulfills a renewal and healing role for several California tribes including the Hupa, Karuk, Wiyot and Tolowa Dee-ni’. The return of the condor will help to repair century old wounds from the past to the indigenous peoples and landscape of the Pacific Northwest.

The California condor is one the most magnificent avian species, with wings spanning nearly 10 feet. It is also one of the world’s longest living birds, with a lifespan of up to 60 years. They soar to heights of 15,000 feet, reaching speeds of more than 55 miles per hour and can travel up to 150 miles a day.

Micro-trash surgically removed from chick

There are currently 488 California condors existing today with 312 in the wild. Populations have been re-established in Arizona with 88 birds, Southern California with the largest wild population of 188 and Baja, Mexico with 36. They are slow to reproduce as they do not reach maturity until six years old. A nesting pair, which mates for life, will give birth to one chick every other year. Chicks are able to fly after six months but continue to roost and hunt with their parents until age two, when they are displaced by new clutch. Condors live in large family groups and have a well-developed social structure.

A combination of DDT, lead poisoning from bullets and poaching put the condor on the federal and state Endangered Species list. Once close to extinction, with only 22 left in captive breeding programs, it was declared extinct in the wild in 1987. With the recent California ban on lead bullets there are high hopes that this reintroduction will last but there is worry should the birds make it to Oregon where lead ammunition is still legal and widely used. While lead ammo is still the leading cause of death in adults, mirco-trash and plastics is one of the leading causes of death in chicks and eggshell thinning from leftover DDT in the environment, known as DDE, is also of concern.

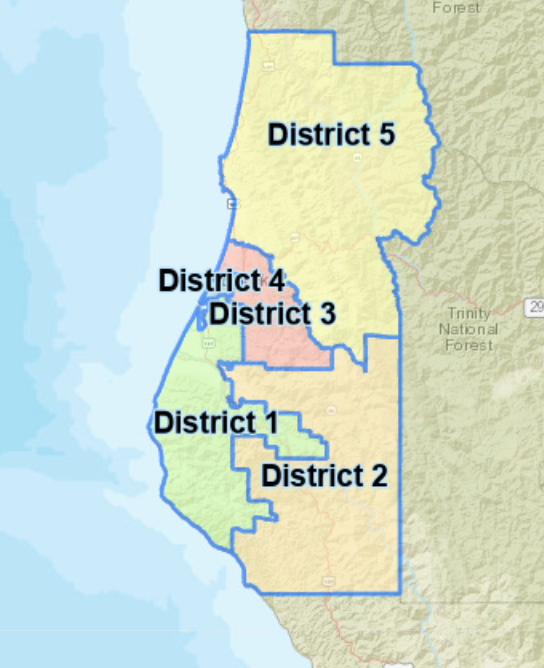

Proposed nonessential experimental population area.

The proposed “nonessential experimental population” outlined under the 10(j) rule of the Endangered Species Act allows for less extensive protections. Simply stated, any birds outside of the experimental population area would be treated as endangered rather than threatened. For instance, here future nest sites would only be given an approximate 650 foot buffer zone. Any activity deemed “fuels reduction” would be allowed anywhere at any time and there are exemptions from liability for electric utilities and wind farms. The proposed population area expands to the entire state of Oregon. Given that the species is still critically endangered EPIC believes that newly made nest sites deserve more protection, especially the first few years and that the population area boundary should be minimized to protect the bird further into its northern range.

Over a century has passed since the nation’s largest flying bird soared among the world’s tallest trees. Once the environmental documents and permits are secured, condors from the Portland Zoo could be in the air over the Klamath River in 2020. The plan is to release six birds a year over 20 years. All are planned to be fitted with transmitters and captured for testing on a yearly basis. We are all hoping that this effort will enable condors to once again flourish throughout the Pacific Northwest.

You can submit comments electronically at: http://www.regulations.gov or by hard copy to: Public Comments Processing, Attn: FWS-R1-ES-2018-0033, Division of Policy, Performance, and Management Programs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, MS; BPHC; 5275 Leesburg Pike; Falls Church, VA 22041-3803.

Comments