Exposed: Post-fire Logging Harms Endangered Owl

- Nov 24, 2015

- 3 min read

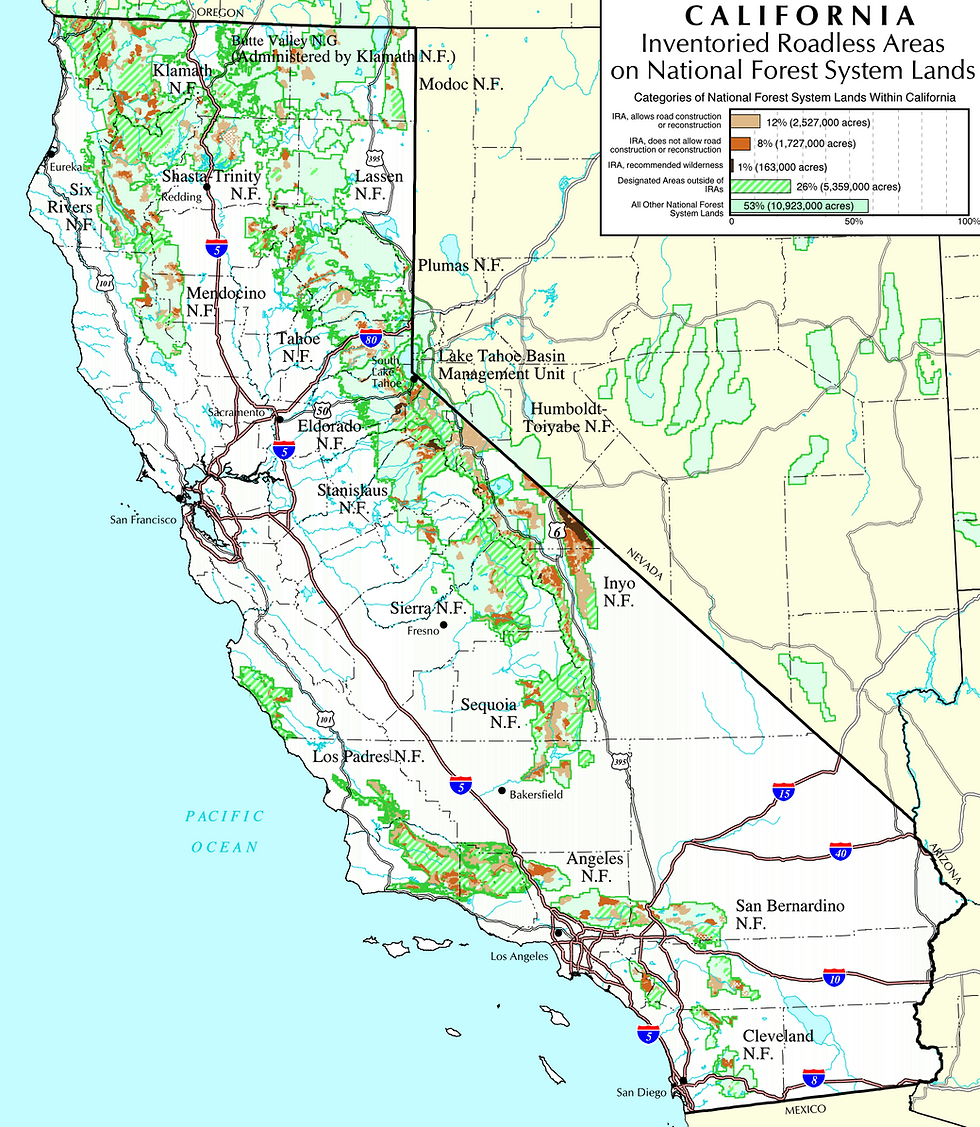

Mixed-severity fire, like that shown, provides functional habitat for northern spotted owls. Photo credit, Scott Harding.

Private landowners, in particular Fruit Growers Supply Company, recently cut thousands of acres of northern spotted owl habitat, likely killing or harming the protected owl in violation of both federal and state law. And they got away with it. Here’s the story of how a timber company likely violated the law and how no one caught it.

Spotted owls utilize post-fire landscapes, including those that burn at high-severity—that is the conclusion of numerous recent scientific papers. High-severity areas, marked by significant numbers of dead or dying trees, provide excellent foraging grounds for spotted owls. The surge of dead wood and new shrub growth forms ideal habitat for wood rats, deer mice, and other spotted owl prey. The standing dead trees, or snags, provide branches for owls to roost while scanning for dinner. And because fires generally burn in a mixed severity pattern, with high-intensity burns close to areas that fire barely touched, there are often nearby trees for the owls to roost. This is informally known as the “bedroom/kitchen” model of habitat usage.

This finding, that spotted owls utilize post-fire forests, is somewhat new. It also runs counter to generalized statements about spotted owl habitat, which has generally been associated with complex mature forests. The Forest Practice Act was certainly written before this was well recognized.

While most logging in California is accomplished through a Timber Harvest Plan (THP), substantial logging can evade the environmental review provided by a THP. Under an “emergency notice,” a timberland owner can clearcut an unlimited number of acres by declaring an “emergency”—a broad loophole, which includes almost all conditions that render a tree “damaged, dead or dying.”

In 2014, the Beaver Fire burned some 32,496 acres, including 13,400 acres of private timberlands in Siskiyou County, much of which is owned by Fruit Growers. Based on the available information, between 2014 and 2015, Fruit Growers filed 32 emergency notices with CALFIRE totaling 8,644 acres. Other nearby landowners similarly filed emergency notices totaling 1,166 acres.

From surveys conducted by the U.S. Forest Service, we know that individual owls were harmed in violation of federal law by Fruit Growers. After the fires but before most logging had begun, a curious male northern spotted owl, identified as KL0283, responded to the hoot of an owl surveyor; he had survived the fire and was living amongst the dead trees. KL0283 was proof that spotted owls utilize post-fire forests.

Sadly, the Forest Service reports later surveys attempting to locate KL0283 after logging failed to yield any positive survey results. The Forest Service notes that logging reduced the owl’s habitat far below minimum acceptable levels, and given the lack of nearby habitat, it was unlikely that he had moved to somewhere better. KL0283 is likely dead, killed by the impacts of logging.

On a facial level, Fruit Growers followed the law—they filed emergency notices telling CALFIRE that they were planning on logging and logged pursuant to those notices. However, upon investigation, it appears that Fruit Growers harmed northern spotted owls in violation of both federal and state law. How was Fruit Growers able to log spotted owl habitat without detection for so long? Turns out, it was pretty easy.

First, it is unclear whether Fruit Growers knew it was violating the law. In each emergency notice, it wrote, “Due to the severity and intensity of stand replacing fire, [the] area can no longer be considered Suitable NSO Habitat.” As explained above, this is a common misunderstanding. By regarding all burned forest as non-habitat, it provided Fruit Growers an easy way to avoid having to evaluate and state the potential impacts to spotted owls.

Second, CALFIRE dropped the ball. It is CALFIRE’s job to evaluate emergency notices and reject any notice which may cause more than a minimal environmental impact. CALFIRE obviously failed at this.

Third, it is unclear whether anyone else was paying attention. It does not appear that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife reviews emergency notices—the Department only recently was able to hire sufficient staff to even review ordinary THPs, let alone emergency notices. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency charged under federal law with the protection of the owl, does not review California timber harvest implementation. EPIC, I freely admit, failed to put the pieces together until too late.

But never again. EPIC is on a mission, spurred by the likely death of KL0283, to reform post-fire logging on private land in California. For more on the environmental impacts of post-fire logging, please visit wildcalifornia.org.

Comments