Chemical Warfare on Native Species

- EPIC Staff

- Mar 4, 2010

- 2 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2023

The study “Atrazine induces complete feminization and chemical castration in male African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis)” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Hayes’ lab found that 10 percent of male frogs treated with low doses of the herbicide became physically female, while the other 90 percent suffered lowered testosterone levels and fertility. Compared to a clean control group, the treated frogs were less successful in mating.

The ‘feminized’ male frogs were fully capable of mating with male frogs, producing eggs that hatched only males – because both parents were genetically male.

In an interview with the SF Chronicle, Hayes suggested that atrazine may not only be implicated in worldwide declines of amphibians, but other species as well. “There is more and more evidence from other researchers,” he said, “that Atrazine is also damaging the immune systems of fish, reptiles and birds.”

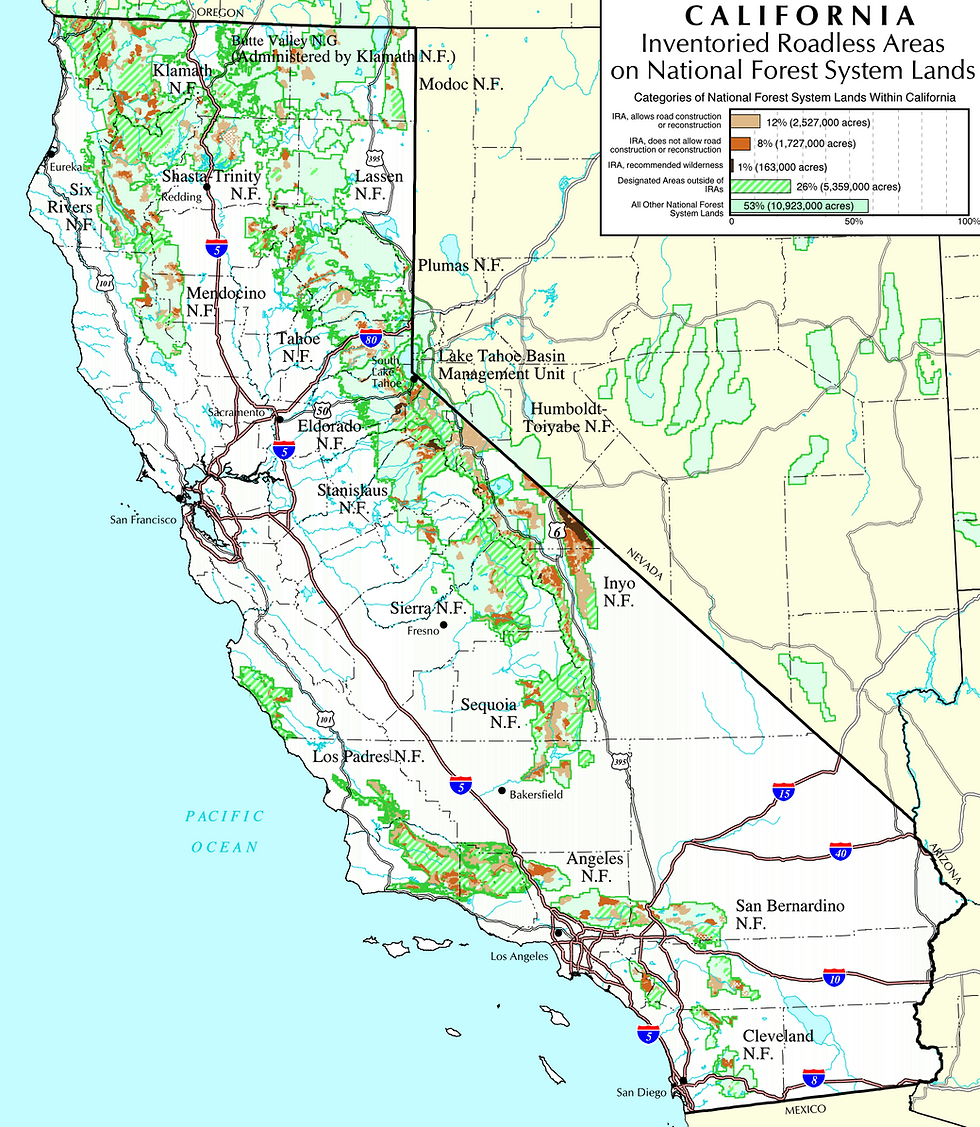

A recent article by the California Native Plant Society’s Jen Kalt in NEC’s EcoNews notes that, according to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation records, an estimated 12 tons of atrazine was used in Humboldt County forests over the last six years.

Atrazine is heavily used in corn production. In a response to the frog study reported in the Washington Post, Lynne Hoot, with the Maryland Grain Producers Association, noted that atrazine use by corn growers, because “about 70 percent of corn and soybeans grown [in Maryland] are now genetically designed to work better with the herbicide Roundup.

Reassuring? Not so much.

Another recent study identified, for the first time, long-suspected synergistic effects from the key ingredient in Roundup and fish parasites. Fish treated with levels of the herbicide previously believed safe and exposed to common parasites at the same time suffered much higher rates of infection than fish not exposed to the herbicide. To cap it off, the snail species that is host to the parasite produced significantly more parasites when exposed to higher, but still moderate, levels of the herbicide.

The study’s abstract concludes, in uncharacteristically strong language for science, “This is the first study to show that parasites and glyphosate can act synergistically on aquatic vertebrates at environmentally relevant concentrations, and that glyphosate might increase the risk of disease in fish. Our results have important implications when identifying risks to aquatic communities and suggest that threshold levels of glyphosate currently set by regulatory authorities do not adequately protect freshwater systems.”

Related Links:

Comments